School counselors provide a variety of services for students in the prekindergarten to grade 12 setting, supporting both students’ mental health and academic achievement.

However, ongoing challenges across the nation to recruit, hire and retain qualified school counselors have caused a massive shortage, particularly in rural schools, impacting students, their families and communities.

UW-Stout’s M.S. in school counseling program “aims to increase the number of school counselors in Wisconsin, which will increase student achievement and create stronger communities,” said Assistant Professor Riley Drake, who, with Assistant Professor Molly Welch Deal, researched the shortage of school counselors in rural Wisconsin areas and how it is affecting children’s access to mental health care.

Through a Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Federal School Based Mental Health Professionals grant, the program is shifting from on-campus to 100% online beginning in fall 2025 to make it more accessible and meet the needs of prospective graduate students.

“We know there’s a high demand for school counselors in rural areas and educators who would love to get a license but can’t make the trip to campus for classes,” Drake said. “The online degree program will help them achieve their career goals.”

According to the National Education Association, U.S. schools are facing a shortage of approximately 300,000 educators and staff. In Wisconsin, 30% of the population lives in rural areas, where the shortage is pronounced.

At the beginning of the 2022-23 academic year, there were 56 school counseling vacancies across the state. Wisconsin is projected to need to fill 1,500 school counseling positions within the next five years, Drake said.

The WDPI grant covers the period of July 1, 2024, to Sept. 30, 2025, in the amount of $156,000. The grant also supports the development of a post-master’s certificate leading to Wisconsin endorsement for licensure in school counseling designed for people with clinical mental health and general education backgrounds to help strengthen the number of school counselors available to young students. It will also support to diversify applications and enrollment to UW-Stout’s Ed.S. in school psychology specifically, and into Wisconsin graduate programs more generally.

Joining the helping field and positively impacting young students

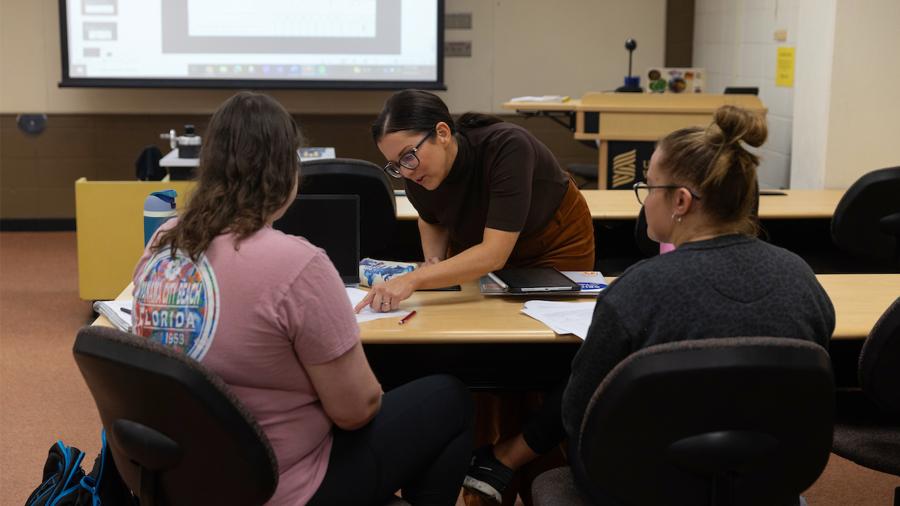

UW-Stout’s polytechnic focus gives graduate students experience working with volunteer clients from childhood to adulthood through clinical experiences beginning in their first year of the program.

Students learn culturally sustaining practices in school counseling, legal and ethical issues, the psychology of development, assessment, school consultation and more, earning their master’s degree in four semesters, with graduates working in the profession in just two years.

Lucas Zuiker, the university’s School Counseling Organization president, chose the program because he had strong leaders and role models in his schools growing up in Marshfield. “They dedicated themselves to education and took the profession very seriously. I hope to emulate that, while also carving out my own identity as an educator,” he said.

By providing his future students with authentic information and practical experience, “whether they want to pursue higher education, the workforce or another path, my goal is to work with them to see what that looks like and help them navigate the challenges and truths of post-secondary life after high school,” he added.

Since arriving at UW-Stout two years ago, Drake and Welch Deal have revised the school counseling program to emphasize culturally responsive and sustaining practices, with a focus on equity and justice.

This focus was the reason Abigail Smith, of Marshfield, chose the program.

“I always wanted to work in the helping field. I chose school counseling because I am passionate about helping underrepresented and marginalized youth and want to be a positive influence to as many students as possible. I want to keep equity and justice at the center of my work so that all students can access the necessary resources,” Smith said.

School counseling incorporates equity and justice more so than other mental health professions, she added, and it uses a holistic approach to help students by incorporating their school, community and family.

“Dr. Drake and Dr. Welch Deal do a fantastic job of incorporating discussions on equity and justice in all aspects of the program. We are pushed to analyze critically the information presented to us and use a social justice framework in our work. The program truly emphasizes the importance of supporting all students we will work with,” Smith said.

Students are required to complete a 100-hour practicum and a 600-hour internship with supervision from licensed professional school counselors and UW-Stout faculty, per Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction guidelines.

Smith’s practicum will be at Chippewa High School. She will graduate in May 2025 and plans to work at an inner-city school in the Madison-Milwaukee area.

Difficulty retaining school counselors in rural areas

Drake and Welch Deal’s research, titled “School Counselors and Rural Cultural Wealth: Exploring Resistance to Abandonment,” incorporated findings from several national and state organizations.

The national Youth Risk Behavior Survey, administered to students in Wisconsin schools every two years, indicated in 2021 that a significant number of youths are struggling with potentially undiagnosed anxiety, depression, self-harming behaviors and suicidal ideation.

In 2022, WDPI noted several factors that affect the retention of school counselors in rural areas, including unmanageable caseloads.

The average school counselor is assigned to nearly 390 students, a number significantly higher than the American School Counselor Association’s recommended ratio of one school counselor to 250 students.

Often in rural areas, the school counselor is the only mental health provider available to prekindergarten through grade 12 students, and their mental health needs are not adequately addressed, Drake said.

“When school counselors are not available, students’ mental health suffers. They also won’t benefit from the advocacy for equitable educational access that school counselors are ethically obligated to provide,” she added.

Cooperative Educational Service Agency – CESA #12, for example, located in Ashland County, includes 17 rural school districts with approximately 14,000 students in prekindergarten through grade 12.

In their research, Drake and Welch Deal found that school counselors are chronically unavailable in CESA #12, where at least six of the school districts have only one or no school counselor available to students.

CESA #12 Director of Special Education and Pupil Services Jennifer Ledin noted that students in two-thirds of school districts need additional mental health support and referrals for counseling. Also, special education services have increased in most of the districts.

Because of the rurality of the area, there are few, if any, community-based mental health services, making the need for school counselors even more critical, Ledin said. Often, school personnel with no specialized training help address the mental health needs of students, including those with alcohol and other drug abuse-related or those who need behavioral discipline referrals.

Welch Deal, Drake and school counseling graduate students will be presenting on Rural Cultural Wealth in School Counseling at the Wisconsin School Counselor Association’s annual conference on Thursday, Nov. 7, in Wisconsin Dells.